I left my father on the bench at the war memorial, talking with the old farmers about crops and rain and the goddamn government. They were the same topics other old men had discussed on the same bench the last time either of us had visited this dusty prairie town a half century earlier. And I doubt much will be different another half century into the future.

This was the closest real town to where I grew up. It had grain elevators, a Co-op store and gas station like other towns closer. But it also had a doctor and a dentist and ten bed hospital. So this was where we came when neighbors or family got stomped by a bull, rolled the pick-up after a Saturday dance or simply gave out from one thing or another.

My dad now lives half a world away. But he’d wanted to come back to find old friends, walk long forgotten streets and see the endless horizon one last time. I was looking for something else. The place where all I’ve become was first revealed to me.

Back when I was 9 or 10 and while my parents visited at the hospital or waited to see the doctor, I’d head for Main Street and a spot that held more magic than any other I could imagine. The drug store.

It was no different from any other store front pharmacy in almost any other North American town. A couple of big windows with venetian blinds to keep the interior cool and a door with a Coca-Cola push bar.

Unlike the stores alongside, there were no hand painted signs of weekly specials. No ads for horses or used cars. Just a mortar and pestle gilded into the glass to let you know they made medicine.

The pharmacist and his potions were in the back, with a couple of aisles leading in that direction that held Smith Brothers cough drops, peroxide, hot water bottles and other stuff I apparently didn’t need to know about.

But I never went to the back nor explored the aisles anyway. Everything I wanted was up front by the counter with the Timex watches and cash register.

I got an allowance of 50 cents a week in those days, augmented by the odd dollar in a birthday card or quarter under my pillow when a tooth fell out. It might not seem like much, but it saw me through. A dime of that fifty cents would buy a big coke from the cooler or a Fudgecicle or a dozen Twizzlers. It was a local tax, placating the clerk so she wouldn’t hover while I figured out how to spend my remaining forty cents.

Mostly she’d take phone calls or work on her nails while I dropped a straw in my coke and chewed it more than sipped as I approached the tall circular rack that was my ultimate goal, a spinning aluminum tower that held magazines, comics and pocket books.

They kept the stuff that wasn’t for kids up at the top, “Popular Mechanics” and “The Ladies Home Journal”. Below that were “Argosy” and “Man’s Life” and “True”. My dad bought “True” because he liked the big game stories. But I liked the covers for “Man’s Life” better.

They featured shirtless guys and semi-shirtless women in impossible situations involving snarling bears or giant snakes or Nazis or all three. Those covers really made you want to flip to the inside pages and figure out exactly how “I Escaped Imperial Japan’s Shark Island Prison”.

Little did I know it was an early lesson in setting up the tease and perfecting the third act break.

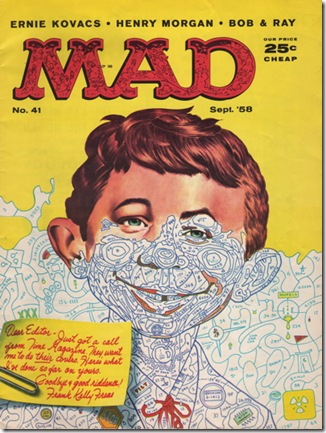

Below these were “Life” and “Look” and “The Saturday Evening Post”, the last always arriving on Friday with a cover painted by Norman Rockwell or somebody trying to look like him. And on the lower racks were “Mad” and “Cracked” and the comic books.

When I first found the drug store, I was already addicted to comic books. Superman was everybody’s favorite, of course. But I gravitated more to Batman, Green Arrow and Blackhawk. They were real guys, heroes you had a shot at emulating, not somebody who only got that way by being from another planet.

Lesson #2: Keep your characters believable.

“Mad” Magazine was my secondary addiction. It was half a comic book but with a cock-eyed point of view that paralleled my own confusions about why the world worked the way it seemed to do. I recognized people and situations I knew in the pages of “Mad” taking some comfort in knowing that Alfred E. Newman’s gang found their importance or self-importance as absurd as I did.

When you’re ten knowing you’re not alone is a precious commodity.

Make the audience feel you understand them and they’ll follow you anywhere.

Parents and teachers had the same opinion of “Mad” as they have of their kids watching “South Park” or “Family Guy” or playing “Grand Theft Auto” today; part of what makes all of those titles a subversive thrill for anybody not yet a teenager. And for whatever harm those kids may suffer from the content, a piece of me senses they’re also being inoculated against what somebody in authority might hope they’ll swallow in the future.

As my first summer at the drug store wore on, I graduated from illustrated pages to collections of letters to Mama by Charlie Weaver and compilations of similar homespun jokes that I could tell at family gatherings.

The humor was probably older than my grandparents, but at least I was reading something that had more words than pictures.

And the future storyteller was learning that people appreciated a certain amount of familiarity as well as a leavening of humor.

But because of the Drug Store, I didn’t graduate from pages of jokes to “Treasure Island” and “Robin Hood”. Those books were readily available on the shelves at school and the library. But they didn’t offer the promised thrills of the paperbacks further up the back of the aluminum carousel.

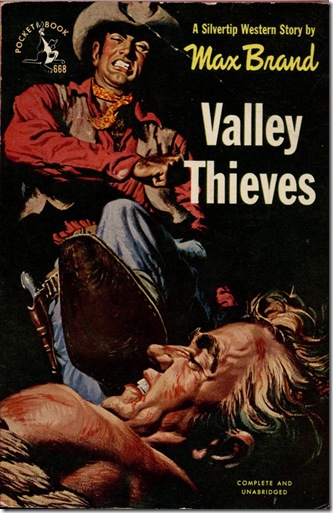

Western novels by Max Brand, Zane Grey and Louis L’Amour were everywhere when I was kid. You’d find them on a work bench at the local garage, piled next to the hired man’s bed or in the “Take one/Leave One” box at any motel. Before televisions were ubiquitous, evenings were passed by everyone from mechanics and farmers to travelling salesmen with a paperback novel.

My parents didn’t frown on my reading Westerns, feeling it was time better spent than watching them on TV. But mixed among those drug store offerings were other novels that would one day earn the genre title of “Pulp”. And the clerk at the drug store was the first line of defence against the spread of their contents. Plop some lurid crime novel on her counter and she wouldn’t even move her eyes off her manicure in progress to let you know your mom wouldn’t want you reading that.

But as every writer knows, offering something “forbidden” is the quickest way to pique an interest.

After two or three tries with covers that didn’t seem as blood-stained as the last rejection, my future career was saved by some marketing genius who’d figured out you could sell some long played out title by gluing it upside down and backwards to a book by some mediocre author nobody was buying.

Two for one – and the clerk at the counter only needed to get the price from the less sensational side.

I carefully held the harmless cover in front of her, paid my 35 cents and tucked the obverse title, a 15 year old novel by some guy named Mickey Spillane, into my overalls.

Some guys will tell you they first had sex when they were eleven. I was introduced to Mike Hammer.

Mike and Mickey changed my life. This was a book where people talked like the people I knew, where why people did some things that were never explained to me became clearer, and from which I suddenly learned what went on behind closed doors.

I guess some kids would have been traumatized by “I, The Jury”. But it energized me and seemed to have the same effect on all the friends who borrowed it, sworn to make sure they never left that side of the book facing upward when they parked it for the night.

As far as I know, it didn’t drive any of us into a life of crime or depravity (although I did end up in show business). And I think that’s because we all sensed that despite the moral ambiguities and shades of grey afflicting the characters we knew we were being told a truth or two about the world.

And above all else an audience appreciates it when you are honest with them.

The street where my drug store sat had been transformed in the 50 years since I’d last been inside. Chain stores had replaced local outlets and the facades replicated some attempt at urban planning and cultural uniformity. It bore a different sign now, but it was still a drug store. And it still had that mixed smell of vanilla and disinfectant that all drug stores seem to have.

The teen at the counter barely gave me a glance as I walked in, busy doing her nails. The two aisles to the pharmacist at the back were still there but the aluminum rack was gone, replaced by a respectable magazine stand neatly organized by subject matter.

There were no men’s adventure magazines and the comics were all Marvel titles. The single shelf of paperbacks contained books proclaiming how many weeks they’d been on the NY Times best seller list. It was the kind of menu you can find at any grocery check out counter.

That didn’t surprise me. There really are no backwoods, out of the way places anymore. We’re all on-line imbued with that old Las Vegas “Everything, All the time” mentality. That morning at a nearby diner, I’d watched a couple of farmers order pesticide on their blackberries and one later assure the dealer he’d fly over in his Cessna that evening to pick it up.

Kids don’t go to the drugstore to find inspiration anymore. And yet…

Tucked amid the best sellers was a copy of “I, the Jury”, its cover illustration modernized and appended with some annotated appreciation by somebody of literary fame or scholarship. I dropped it on the counter along with a box of Fudgecicles for the guys at the war memorial. The clerk couldn’t have cared less what I wanted to read. For the second time in a half century, I tucked some guy named Mickey Spillane in the pocket of my jeans.

That night at the motel, I thumbed a few chapters as my father slept and then, as we should all do with the books we love instead of relegating them to a shelf, I tucked it into the bedside drawer behind Gideon’s Bible.

Maybe some night soon, a travelling salesmen disinterested in watching either “Survivor” or “The World’s Biggest Loser” will find it. Or maybe it’ll be some 11 year old boy with a dead Gameboy battery and nothing else to do.

There’s always somebody in need of a story.

0 comments:

Post a Comment