It was a dreary Sunday afternoon in Vancouver sometime in 1974. I was shooting my 3rd or 4th feature, "The Supreme Kid", playing a character who was in virtually every scene. It was a low budget movie, probably under six figures, and we worked six day weeks in what felt like continuous freezing rain.

Sunday was our one day off and I should have been sleeping. But another Canadian movie had opened that week, a really big and very important one called "The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz".

I'd read the book, one of Mordecai Richler's first novels, in high school and loved it. Who wouldn't. It was the sprawling, brawling and funny story of an underdog Canadian kid trying to make good that deserved every bit of its stellar reputation.

Everybody in the Canadian film business in 1974 knew that "Duddy Kravitz" was an important film.

It had a million dollar budget. It was based on one of the most important novels in Canadian literature at a time CanLit was dead center of the International spotlight. It was going to be our burgeoning film industry's "coming of age" movie. Our chance to show the world what we could really do.

But because it cost so much and carried such a literary pedigree and heavy cultural import, it absolutely had to succeed. It needed to be not only an artistic triumph but a financial one as well. It needed to be assured of being seen all over the world.

So the producers hired a mostly American cast.

It wasn't a stellar group of actors by 1974 standards, although everyone involved was immensely talented.

Duddy was played by Richard Dreyfuss, fresh from "American Graffiti" but still far from a star. His father "Max" was played by Jack Warden with the remaining major roles assumed by Randy Quaid, Denholm Elliott, Zvee Scooler and Joseph (Dr. No) Wiseman who, while Canadian born, hadn't lived in the country since he was a kid.

The lone Canadian actor in a major role was Micheline Lanctot as Duddy's French Canadian girlfriend Yvette.

The casting was a bitter pill for many Canadian actors to swallow. Everyone knew there were Canadian actors just as capable, maybe even more talented than those assuming the roles of quintessential Canadian characters.

We were all used to losing roles to actors nobody had ever heard of from New York or London. That even happened on one hour dramas made by the CBC or guest shots on "Police Surgeon".

I guess we thought "Duddy" would be different. We'd helped create the industry that now seemed ready to take on the world. The novel was so much "of" the country. This should have been our coming out party too.

But it wasn't.

I thought "Duddy Kravitz" was an okay film and left the theatre hoping it would do well.

But I couldn't shake the feeling that we'd been robbed of our "Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith" or "Gallipoli". Some part of us and our culture had been appropriated and sacrificed on the altar of future promises -- promises that seldom came true -- and never did when a great Canadian novel was involved.

Margaret Atwood's "Surfacing" arrived on screen starring Joseph Bottoms and Kathleen Beller. The same writer's acclaimed "The Handmaid's Tale" featured Natasha Richardson, Faye Dunnaway, Aidan Quinn, Elizabeth McGovern and Robert Duvall.

Elsewhere in the world, Canadian actors such as Donald Sutherland, Victor Garber and Christopher Plummer were deemed worthy of opening films with much more money and reputation riding on their success or failure.

The same courtesy and consideration was denied them at home.

Richler's next novel to reach the screen was "Joshua Then and Now" in 1985, starring American actors James Woods and Alan Arkin.

By now, we were through the Wild West fly-by-night tax credit days of Canadian film history and were establishing ourselves on the world stage. But still -- Canadian actors weren't playing the Canadian characters in our best literature.

We were still being told by producers and the now pervasive bureaucrats from Telefilm Canada, the federal government's financing arm, that we needed those big names from Hollywood to sell the idea that we could do quality work and reduce the risk of the many millions these films were now costing.

In their own country, Canadian actors still couldn't be trusted with anything but supporting roles when work of cultural importance was at stake.

In Hollywood, Canadian actors like Dan Aykroyd, Michael J. Fox and William Shatner were the faces of tent pole studio features and major film franchises. But somehow the DNA of their Canadian brothers and sisters was consistently deemed too weak to tackle the international box office.

It's a process that has largely continued while dozens of Hollywood features risking hundreds of millions of dollars apiece have opened on the shoulders of such Canadians as Keanu Reeves, Carrie Ann Moss, Jim Carrey, Kim Cattrall, Mike Myers, Natasha Henstridge, Martin Short and Pamela Anderson.

Yet -- every time a great Canadian novel readies its debut, the Canadian characters that Canadian actors could play are once again replaced by Americans deemed more capable of capturing attention and alleviating risk.

Thirty Seven years after I stood in front of that Vancouver movie theatre in the rain contemplating the poster for "The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz", I stood in the Sunday rain in front of the poster for "Barney's Version".

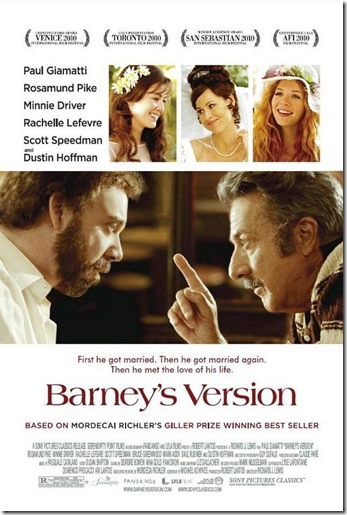

For all I know it was even the same theatre, although a multiplex now. The actors listed on the poster as the major players were Paul Giamatti, Dustin Hoffman, Rosamund Pike and Minnie Driver. To be fair, Canadian actors Rachelle Lefevre and Scott Speedman were named as well, but my understanding is that they're in much smaller supporting roles.

Now there isn't a bad actor in that whole bunch. But I began wondering just how many generations of Canadian actors will have to pass before one of our own gets to play one of our own in a feature film many in the rest of the world will use to form an opinion on who "we" are.

I also began wondering if this isn't so much a talent thing or a well-known name thing so much as its a class thing.

Michel Roy, the CEO of Telefilm, is on record as saying that the only way a government funded film industry can succeed is if we get rid of the Canadian actors.

It's an odd point of view to take, telling taxpayers their kids can't cut it but they still should fund an industry that considers them second class citizens.

It's doubly odd when studios and networks in Los Angeles were rolling out their new television series last week, many of which featured Canadian actors in leading roles who've given up on their home country.

How is it that actors who can't buy work in Canada are so regularly snapped up on their arrival in Hollywood?

We don't have the years of intense training of the Brits or the tanned bodies and perfect teeth of the Australians, two countries that would never think of having their well loved literary characters played by imported talent.

These people are simply good at what they do. Just as good as the good actors that any nation produces.

But those in charge of the Canadian film industry don't think of them that way.

Am I wrong in suspecting that those of the powers that be, the ones who "don't watch television" and "mostly see art films" but who are always aware of who's up for the Giller Prize, want their beloved classics to come to the screen with a cast that will affirm their worth in the same way that Ben Mulroney creams himself whenever somebody mentions Winnipeg in a movie?

Is the oft noted "national inferiority complex" -- the complex nowhere visible during the 2010 Vancouver Olympics or in most other Canadian endeavors -- actually an affliction of only our ruling and chattering classes?

The argument that you need big names to sell your movie overseas is just as specious as claiming we're home to a diluted talent pool. The reality is that the most successful films in foreign markets feature either complete unknowns or names unknown to the locals.

And to be completely honest, if name value were such an essential selling point, then "Duddy Kravitz" and "Barney's Version" should have been marketed in book form as the work of John Updike or Stephen King. They'd have sold far more copies.

Film has long been recognized as a collaborative art form. We're all in this together. And that means that you don't have a real Canadian film industry without Canadian actors.

And you don't have a recognizable culture when the faces of your homegrown heroes are those you remember as "John Adams" or "Bernie Focker".

I decided I wasn't in the right frame of mind to see "Barney's Version" and turned to the poster next to it -- "Blue Valentine", an American film starring Canadian actor Ryan Gosling that's already garnered rave reviews and grossed five times what "Barney's Version" has earned for its producers.

We never get it right. No matter how much we have going for us.

We always sell ourselves short.

0 comments:

Post a Comment